Associate Professor Chris Danforth uses Twitter to occasionally share scientific research, post photos of his golden retriever, or upload videos of himself biking to work in the snow.

But more than anything, he uses Twitter to learn about the public’s collective well-being.

Danforth arrived at UVM in 2006 to join the Vermont Complex Systems Center, which crunches data and looks for patterns. Danforth and UVM Professor Peter Dodds eventually teamed up to start the Computational Story Lab at UVM, which sifts through public data—including social media—to discern the stories shared online.

Danforth’s research about measuring health and happiness on social media has received worldwide attention. His work has focused on everything from how Instagram photos can be a predictive marker for depression to how exposure to urban parks improves affect and reduces negativity on Twitter.

While the honeymoon with social media—Facebook, in particular—is over, he believes that data being amassed on social media means that mental health is on the verge of a digital revolution.

“It’s a really exciting time to be working on problems related to human behavior and have access to information that can help us be happier and healthier,” says Danforth, PhD, an applied mathematician whose background is in weather prediction.

Just as a sophisticated collection of data can help meteorologists predict hurricanes a week in advance, information that people are sending from their phones can reflect how they are feeling.

“We’re carrying around computers in our pockets every day, and the data coming from the different signals that we choose to send—whether it’s the words we share with each other in text messages or with the public on social media—they reflect a lot about our thoughts, opinions, and feelings about what’s going on for us and for the world,” he says.

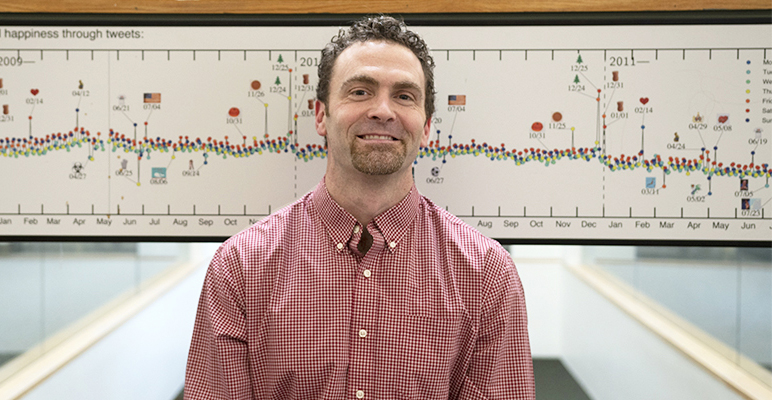

At the Computational Story Lab, home to the Hedonometer, an instrument that measures on Twitter the happiness of large populations in near real time, Danforth, Dodds and researchers are working to build instruments and turn all of that data into useful public health signals.

For example, Danforth and his team are talking with doctors at the University of Vermont Medical Center about building a screening tool for the emergency room. The screening would involve asking people whether they would be willing to have an algorithm examine their social media history.

Danforth explains that if someone comes into the emergency room and is exhibiting symptoms of self-harm, the hospital needs to decide how to help that individual. That intake process currently can take up to an hour of a professional psychiatrists’ time. However, a piece of software that is in development would determine if an individual would need to meet with a psychiatrist. The contribution from Danforth and his team would be to add a social-media based component to risk assessment for self-harm.

“Suicide risk prediction has really not changed in 50 years. It’s one of the great unsolved problems in social science,” Danforth says. “With weather prediction, we’ve been marching our way forward because we have much better data, and we have equations and physics. But given how difficult suicide risk prediction is, the idea of using these other sources of information aside from just asking a person how they’re doing, that’s appealing to us.”

Embracing Privacy, Measuring Happiness

Data mining and election interference on social media have dominated the headlines over the past couple of years. Even though much of what is posted on social media is helpful to Danforth’s research, he supports changes to support online privacy.

It’s one thing to have Amazon show you a product you might like based on your previous purchases and quite another to feel like your voting patterns are being manipulated.

“It’s definitely time for people to start thinking more carefully about how their data is used. I’m in support of regulations being developed to help control how our social media data—and other types of data, such as our genetic history and our family health history—are used by corporations,” he says. “It’s something we talk about all the time here because we want to build technologies that will help empower people to be happier and healthier in their life. Yet if those technologies are deployed by nefarious actors, technologies like that could end up hurting people.”

For example, he says, take the emergency room screening tool. An individual may not be in the best state of mind to decide whether they should have their social media data viewed by an algorithm.

“How much access to what’s going on in our head should companies have or should doctors have?” Danforth says. “In the case of somebody who’s in crisis, you want to figure out how to help them.”

A Data Science Partnership

Last fall, MassMutual Life Insurance Co. gave UVM a $5 million gift, the largest donation the school has ever received from a corporation. The gift will bolster the Complex Systems Center, which is part of the College of Engineering and Mathematical Sciences and aims to improve the world through data science and analysis. The data science initiative with MassMutual represents the largest single corporate collaboration with the Center since its inception in 2006.

“We’re very excited about this. We have new degree programs, an undergraduate in Data Science and both MS and doctoral programs in Complex Systems and Data Science,” Danforth says. “The goal is to train students and have them go into world, with an ethical and moral compass, to take the data that we produce and use it to help people.”

The ‘Dow Jones Index of Happiness’

Danforth is also working to create a suite of instruments for people working in public health. His flagship instrument is the Hedonometer, which measures tweets to see how the world is doing.

When the Hedonometer (dubbed the “Dow Jones Index of Happiness”) launched a decade ago, Danforth says it measured a very regular up and down cycle. Weekends were happier and the earlier part of the week was sadder.

“That was a very robust wave for the first seven or eight years we had it running,” he says. “Around the time since the election cycle, it broke down and has maintained a disorganization largely over the last few years. That’s not something we expected to have happen. The news cycle and political environment is why we see a lot less emotional regularity.”

Words like “not,” “can’t” “don’t,” and “won’t” were at one time more commonly used on a Monday or Tuesday. But now Danforth sees those words appearing more evenly every day of the week.

Some of the happiest days of the year in 2018, according to the Hedonometer, were Valentine’s Day and Christmas Day. Some of the saddest were the school shooting in Parkland, Florida, and Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court confirmation.

Danforth stopped using Facebook a few years ago and isn’t much of an Instagram enthusiast. Outside of work, he mostly uses Twitter to stay up-to-date with research and current events (and to share the occasional fun video or dog photo).

“I don’t use Twitter so much to express how I’m feeling,” he says. “One of the problems with social media is feeling like you’re missing out. In general, we all need to think more about what is good for our emotional and mental health, and whether (social media) is really helping. Yes, social media is free. But you’re paying, obviously, with your attention.”

The “UVM Is” series celebrates University faculty, educators, and the campus community.

To learn more, visit UVM Continuing and Distance Education at learn.uvm.edu.