On Tuesday, voters in Washington State voted down a ballot measure to require labeling of foods containing genetically modified ingredients. The measure was similar to a bill defeated in California last year, and if it had passed, it would have made Washington the first state in the nation to require GMO labeling. However, the whole affair played out in the typical fashion of most agribusiness vs. grassroots initiatives: whoever spends the most gets the votes. Whether you support GE labeling or not, a critical analysis of the campaign raises some interesting questions about the efficacy of labeling initiatives and the role of money in political campaigns.

On Tuesday, voters in Washington State voted down a ballot measure to require labeling of foods containing genetically modified ingredients. The measure was similar to a bill defeated in California last year, and if it had passed, it would have made Washington the first state in the nation to require GMO labeling. However, the whole affair played out in the typical fashion of most agribusiness vs. grassroots initiatives: whoever spends the most gets the votes. Whether you support GE labeling or not, a critical analysis of the campaign raises some interesting questions about the efficacy of labeling initiatives and the role of money in political campaigns.

By way of some background: we know that most Americans are concerned about GMOs. A New York Times poll conducted earlier this year showed that 93% of Americans favor labeling foods that have been genetically modified. But when the Washington votes were tallied, the numbers added up very differently: 46% favored labeling, while 54 percent opposed it. So what happened? Let’s look at who contributed to the debate, and what they had to say about it.

The “Yes” camp: The proponents of the bill, the “Yes on 522”campaign, focused on consumers’ “right to know” what is in their food. The “Yes” campaign raised just under $8 million. Contributions from 10,000 Washington State residents accounted for 30% of that total. The remaining 70% was from out of state (donors included Dr. Bronner’s Magic Soaps and the Center for Food Safety in Washington, D.C).

The “No” camp: The opposition, however, handily outspent the proponents of the bill. The “No on 522” campaign raised $22 million, mostly from agribusiness. Only $550 of that total (yes, that’s five hundred fifty dollars) came from Washington state residents. The rest came from out of state agribusinesses, primarily the Grocery Manufacturers Association (GMA), Monsanto, DuPont Pioneer, and Bayer CropScience. The messaging of the “No” campaign focused on how labeling could increase food costs and the “arbitrary” nature of the labeling requirements (specifically, what was exempt).

Interestingly, therein lays an important distinction in the failed Washington State initiative: only products actually containing GMO ingredients would have required labels. This means that meat and animal products from livestock fed GE crops would not require labels. The products that would have required labeling included foods like sweet corn, papaya, cold cereals, corn chips, soy milk, canola oil, soft drinks and candy.

Interestingly, therein lays an important distinction in the failed Washington State initiative: only products actually containing GMO ingredients would have required labels. This means that meat and animal products from livestock fed GE crops would not require labels. The products that would have required labeling included foods like sweet corn, papaya, cold cereals, corn chips, soy milk, canola oil, soft drinks and candy.

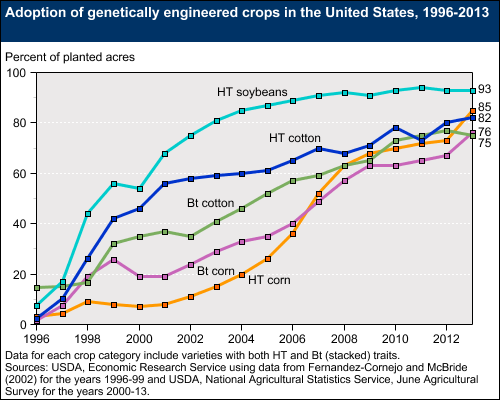

But we know that that the majority of GE crops don’t end up as human food. 93% of the soy and 88% of the corn grown in the US has either (or both) glyphosate resistance and Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) traits, and the vast majority of those crops (98% of soy and 88% of corn) is destined for livestock feed and non-food industries. So the Washington labels would have been useless to any consumers primarily concerned about the ecological impacts of these traits. (That said, given the prevalence of GE feedstock, it’s pretty safe to assume that any meat or animal products from livestock that were not grass-fed or certified organic have eaten GE corn and soy.)

The proponents of the Washington initiative indicated that the labeling exemptions are consistent with international labeling standards (over 60 countries in the world have mandatory GE labeling laws), so as not to put Washington State at an economic disadvantage. But the opposition was quick to point out these apparent inconsistencies in the bill’s exemptions.

So what can we learn from this experience? For one thing, the arguments on both sides focused more around what’s IN the food, rather than HOW it’s produced, even though current science tells us that the environmental impacts from GMOs are likely more severe than risks to human health. Secondly, even though the bill would not have required labeling for the vast majority of products made from GMOs (namely, corn and soy in livestock feed), the agribusiness pocketbook spilleth over with ready money to fight these initiatives. As in California (where the opposition raised $44 million, while proponents raised only $7.3 million) the GE industry was willing to pay the price to prevent Washington from setting a precedent for GE labeling.

Meanwhile, legislative efforts for GMO labeling continue in other states across the country. Connecticut and Maine have both passed bills that will require labeling when other Northeast states pass similar bills. And what’s happening in Vermont, you might ask? Check out my interview with David Zuckerman and the VT Right to Know GMOs campaign.