By Jan Carney, MD, MPH, Professor of Medicine, Associate Dean for Public Health at the University of Vermont

None of us can turn on the news, open a newspaper, or turn on our computer without hearing about Ebola. Many daily questions (and controversies) surround Ebola preparedness in the United States.

What is the status of Ebola in West Africa?

As of October 15, 2014, there are 8,997 reported Ebola cases and 4,493 total deaths in West Africa, based on information from both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and World Health Organization.

What is Ebola? Where did it come from? How bad is the epidemic?

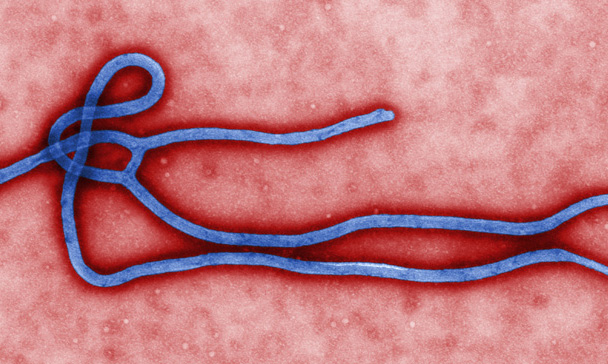

Ebola (formerly called Ebola hemorrhagic fever) is a serious and often-fatal virus infection that causes disease in humans and non-human primates, such as monkeys and gorillas.

Scientists believe bats are the reservoir for Ebola viruses, with animal epidemics (called epizootics) occurring occasionally. Humans can become infected through contact with a bat infected with Ebola virus or through an infected wild animal. Spread of Ebola virus from human-to-human occurs in Ebola virus epidemics. CDC has an excellent graphic that shows how this cycle works.

Ebola was first discovered in 1976 near the Ebola River in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Since then, outbreaks have appeared sporadically in Africa (see map). The 2014 epidemic is the largest Ebola epidemic to date. An updated map shows areas of active transmission in West Africa, and how this is changing.

What are the symptoms of Ebola? How contagious is it?

Symptoms of Ebola infection include fever greater than 101.5 degrees, severe headache, muscle pain, weakness, vomiting and diarrhea, and in some cases unexplained bleeding. These may appear between 2 and 21 days after exposure to Ebola.

Ebola virus may be found in blood and body fluids. Ebola is spread by direct contact with blood or other body fluids of a person with symptoms of Ebola. Direct contact means that body fluids (blood, saliva, mucus, vomit, urine, or feces) from an infected person (alive or dead) have touched someone’s eyes, nose, or mouth or an open cut, wound, or abrasion. Ebola is killed with hospital-grade disinfectants (such as household bleach). Ebola is not spread by air or water.

No FDA-approved treatment is available, and patient symptoms are treated. Ebola is a serious and often fatal disease with death rates about 70 percent in the West Africa epidemic, but fatality rates can be as high as 90 percent.

Forecasts in West Africa

The CDC, using dynamic modeling, estimated 21,000 cases in Liberia and Sierra Leone by the end of September 2014 and 1.4 million by January 2015, if no effective interventions were used. More recently, the WHO projects a potential 10-fold increase in cases by December, to as many as 10,000 a week. Recent editorials in the NEJM warn us that, “Without a more effective, all-out effort, Ebola could become endemic in West Africa, which could, in turn, become a reservoir for the virus’s spread to other parts of Africa and beyond.” Other experts characterize the importance of an effective Ebola vaccine, something currently in accelerated development, as “An Urgent International Priority.”

What is the role of public health?

Public health includes the federal CDC, state health department, and local health departments in many states. Principal approaches are disease tracking (surveillance), case finding and isolation, tracing contacts to stop further transmission, educating health professionals to ensure strict infection control practices are followed, and educating people in the United States and West Africa, especially the general public.

Public health’s role in tracking and preventing Ebola is similar to approaches used for other infectious diseases, but tailored to the specific route of transmission and severity of the Ebola infection.

What are CDC officials doing?

The CDC has more than 160 staff currently in West Africa, have a 24/7 Emergency Operations Center (EOC) activated at Level 1, the highest level. In the United States, in addition to their other Ebola-related activities, they are focusing on health care worker training and protections.

How can we protect health care workers?

Rebounding from questions about how the first person with Ebola in the United States was managed, health care and public health officials received more questions after a second nurse caring for this patient in Dallas, was diagnosed with Ebola. Questions, were all debated in the national media, such as: Did the hospital follow guidelines? Were the guidelines sufficient? Should changes be made?

The CDC publishes extensive information for health care workers and hospitals. They have dramatically increased their efforts to help U.S. hospitals with additional training, and updated guidance on personal protective equipment.

Making sure protective equipment is used correctly every single time is not an easy task. There is a specific sequence of steps to put on and remove personal protective equipment (such as gown, mask, goggles or face shield, and gloves) to minimize the chance that health care workers will accidentally contaminate themselves with infectious material during the process. It takes practice, and experts are recommending that people are watched by a “site supervisor” while doing all of this, a “second pair of eyes,” looking for and preventing any missteps that might put a health care worker at risk for infection.

The New York Times published interactive pictures of recommended protective equipment, including videos of the precise and necessary way to remove it, to prevent contamination and possible infection.

How worried should we be in Vermont?

The Vermont Department of Health reminds us that health care providers need to “think Ebola” and ask about patients’ travel history, and practice personal protection and infection control measures in advance. Public health and health care professionals, from hospitals and emergency departments to outpatient offices and clinics, are working together on a day-by-day basis to be prepared for the unlikely event that we see a patient with Ebola in Vermont.

How likely is it? Dr. Patsy Kelso, our Vermont State Epidemiologist, recently said, “There are tens of thousands of people who travel to the U.S. in a year, so one of them could travel to Vermont. I don’t think it’s likely, but it’s definitely possible.” Which is exactly why the Department of Health is working diligently with all Vermont hospitals and health professionals to be prepared for a rapid response, just in case.

Where can I get more information? What should I be looking for?

It is essential to get information from reputable sources. Both the CDC and WHO publish evidence-based information that is regularly updates. The WHO publishes regularly updated Situation Reports. Although the accuracy and tone of media reports varies, reporting from The New York Times has been consistently accurate, and articles contain links to the original sources of information. In Vermont, the University of Vermont Medical Center Infectious Disease experts also provide information on HEALTHSOURCE, the hospital’s health care blog. The Vermont Department of Health has Vermont-specific information, based on the best science and public health practice.

Jan Carney, M.D., M.P.H., is associate dean for public health at the University of Vermont. She is director of the UVM Master of Public Health Program.