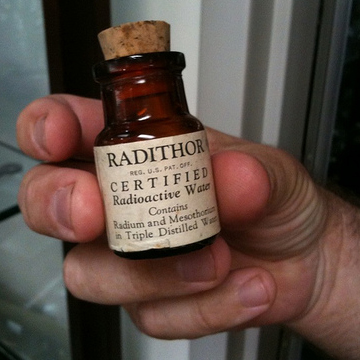

Late one November afternoon, Eben Byers was heading home to New York from Massachusetts. He had just finished watching Yale skunk Harvard 14-0 in their annual football game. On the ride back, Byers injured his arm. Several weeks later, he was still in pain. A medical professional recommended Radithor.

Late one November afternoon, Eben Byers was heading home to New York from Massachusetts. He had just finished watching Yale skunk Harvard 14-0 in their annual football game. On the ride back, Byers injured his arm. Several weeks later, he was still in pain. A medical professional recommended Radithor.

At first, Byers felt great. He drank a few bottles of Radithor every day for two years. Then, something changed. Byers lost weight. He complained of headaches. His teeth started falling out. The next year, his entire upper jaw, except two front teeth, and most of his lower jaw were gone. Holes formed in his skull. His bone tissue disintegrated. A short time later, Byers was dead.

Radithor, it turns out, contained radium, a highly radioactive element. Over the course of several years, Byers consumed enough radium to kill four people. Everyone knew Radithor was radioactive. In fact, selling it was legal. Why did the government allow Radithor to be sold at all?

The answer: this was before 1938. What happened that year? Congress passed the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, and the progressive President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed it into law. The Act gave the Food and Drug Administration real teeth (no disrespect to Mr. Byers). Would anyone in America today quibble with the government ensuring products containing highly radioactive substances are kept off the shelves? Probably not. But what if—under the banner of food safety—the FDA regulates how a farmer grows a tomato? Would anyone complain? You bet. As I posted on this blog last year, the FDA is doing just that with its food safety regulations drafted under the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA). So, are regulations good or bad? As you might expect, the answer is complicated.

Let’s back up—I’ve laid out some concepts that many of us take for granted. Pop quiz from civics class: what type of governmental body is the FDA? It’s an administrative agency housed in the Department of Health and Human Services. It makes regulations, sometimes called rules. A statute, or Act, gives FDA the power to draft those regulations. But what is an administrative agency? More importantly, what power does an agency have?

The answers are crucial for understanding how the United States functions today. Scratch the surface and you uncover a fiery debate over the most fundamental questions our democracy has faced since the founding. Until you grapple with those questions, you can’t truly appreciate the vital argument playing out over FSMA.

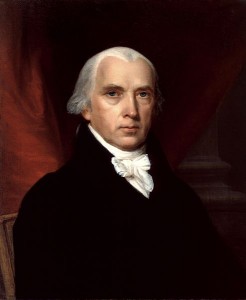

The Founding, or an Exercise in Greed

James Madison knew something about people. They’re greedy. To frame it in a better light—they’re ambitious. In the Federalist Papers, he wrote, “Ambition must be made to counteract ambition.” In a nutshell, that sums up why Madison and the rest of the Founders crafted three branches of government—legislative, executive, and judicial. Each has separate powers and checks and balances the other two. He didn’t imagine the young country as some utopia. Oh no, Madison knew that if our government lacked an internal mechanism to check its own power, it would—through ambitious individuals—eventually wield that power against its own citizens. Voila! Separation of powers and checks and balances

James Madison knew something about people. They’re greedy. To frame it in a better light—they’re ambitious. In the Federalist Papers, he wrote, “Ambition must be made to counteract ambition.” In a nutshell, that sums up why Madison and the rest of the Founders crafted three branches of government—legislative, executive, and judicial. Each has separate powers and checks and balances the other two. He didn’t imagine the young country as some utopia. Oh no, Madison knew that if our government lacked an internal mechanism to check its own power, it would—through ambitious individuals—eventually wield that power against its own citizens. Voila! Separation of powers and checks and balances

Another key principle that keeps the federal government from gobbling up everything in its path is federalism. The problem in the mid-1780s was that the new United States government was too weak under the Articles of Confederation. Our country was like a bunch of separate states with no glue to hold them together. The new Constitution established a much more robust central, or federal, government. But it specifically enumerates what powers the federal government has. If the power is not enumerated—listed in the Constitution—the federal government doesn’t have it. Who holds the rest of the power? The states or, sometimes, “we the people.” This is federalism—the idea that power is split between the central government and the states.

Brilliant, right? Sure, but wait, what does this have to do with food? Hold on! We’re getting there!

America Grows Up—Democracy? Bureaucracy?? Kleptocracy???

Enter the administrative agency. It’s a governmental body typically housed in a department in the executive branch. The United States has had agencies since the early days, but what became known as the administrative state really got going under FDR.

The thing about checks and balances is that it’s great for gridlock. By design, it ensures a contemplative repose for passing laws—better to ensure no big and fast power grabs. But FDR wanted action to get this country out of the Great Depression. He saw the federal government locked in partisan wrangling, courts as slow and regressive, and states as inadequately protecting people’s rights. Agencies seemed like just the fix—people within government who are independent, expert on technical matters, and not swayed by dollars or power.

Here’s the problem. Agencies enforce regulations. But they also write regulations, which have the force of law. And they sometimes adjudicate cases about those regulations. For the most part, agencies are staffed by people the President selects. This means agency staff are not elected—they are not accountable directly to the people. See where this is going? Administrative agencies essentially have all three governmental powers—passing laws, enforcing laws, and judging conflicts based on those laws. What’s more, they can enforce those laws against the states, threatening federalism principles. And they’re not even elected. Yikes! Isn’t this the very aggregation of power Madison wanted to avoid?

But because agencies are staffed by experts and are not voted into office, they can—in theory—quickly and efficiently respond to the myriad complex problems our country faces (think cross-state pollution, interstate transportation, or food safety).

Are these just the kind of progressive governmental bodies our country needs to be a flourishing democracy? Or does the so-called administrative state threaten to bog us down in a bureaucracy—government run by unelected administrators? Or worse, are agencies actually just out to grab power and wealth—a kleptocracy? You guessed it—it’s complicated.

Byer’s Redemption or Small Farmers’ Demise?

Let’s get back to our food system. Contaminated food sickens millions of people every year. Congress responds by passing the Food Safety Modernization Act. FDA is charged with writing the many regulations that determine how the FSMA works on the ground.

Good, right? Huge interstate problem. State governments are too weak to handle it on their own. The content is too technical and time consuming for Congress to respond adequately. FDA—an administrative agency—is just what the doctor ordered. Independent, technically expert, and immune from partisan wrangling. No more death by radium . . . or, in this case, E. coli?

Not so fast. How did the technical experts at FDA draft the content of those regulations? They relied on the agricultural industry. But who in that industry? Those who had the time, money, and resources to afford to play—industrial-scale agribusiness. Not the small family farmer in New England. The result is a suite of regulations that do not match the needs of small farms, thereby threatening their very existence. So, no more fresh, local, sustainably grown food?!

Stay tuned for Part II! We’ll try to get to the bottom of this debate—at least as far as the FSMA regulations are concerned. I’ll explore where things stand now and how you can help write history.

Ben is an attorney and Rhodes Fellow with the Conservation Law Foundation in Portland, Maine. Learn more about CLF’s work with farms and food.

Photo Credits

Radithor Radioactive Water by Frank Guber via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Portrait of James Madison by John Vanderlyn from The White House collection

produce by rick via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)