I recently had the chance to speak with Susan Vaughn Grooters, an alumna of the UVM Department of Nutrition and Food Sciences, about her current work at the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI). Here is a summary of our engaging discussion about the serious threat to human and animal health posed by the use of sub-therapeutic antibiotics in animal agriculture.

I recently had the chance to speak with Susan Vaughn Grooters, an alumna of the UVM Department of Nutrition and Food Sciences, about her current work at the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI). Here is a summary of our engaging discussion about the serious threat to human and animal health posed by the use of sub-therapeutic antibiotics in animal agriculture.

When I started my conversation with Susan by asking her about her career path, she responded back with a question: “I like to ask, ‘what gets you out of bed in the morning?’ I see grave injustices in our food supply. The reason I get up every morning is that I feel driven to do something about them.”

For Susan, those grave injustices revolve around foodborne illnesses, and what she sees as a negligent lack of oversight on behalf of the federal government regarding food safety. “There are fifteen agencies that oversee food safety in this country, and there’s a real breakdown in data sharing, analysis, and communication between those agencies. There’s been a push for a long time for a single food safety agency, but we haven’t seen that materialize yet.”

Susan’s work focuses on antibiotic resistance—the emergence of bacterial strains that do not respond to certain antibiotics—in foodborne illness outbreaks. “CSPI is the one organization that has tracked antibiotic resistant outbreaks to look at attribution (what’s causing them). We’re looking at the data to understand whether antibiotic resistant foodborne outbreaks have higher hospitalization rates. If we can show causality, we can move into doing something about antibiotic resistance in the food supply.”

So what’s causing antibiotic resistance? “From the 10,000 foot level,” Susan explains, “there are a ton of issues, from farm to fork. Most people, when they see cellophane wrapped chicken, don’t think about how it was produced. Our job is to open the doors on the CAFOs [confined animal feeding operations] and slaughterhouses to show how food is manufactured. There’s nothing pretty about how food animals are raised in this country. Chickens are so heavy they can’t walk. Animals are cramped, living in their own filth and manure.”

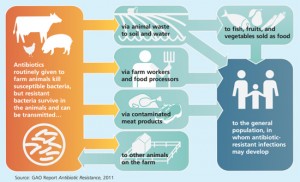

With so many animals in an unhealthy environment, the transfer of disease is especially common. So CAFO managers dose their animals with low levels of antibiotics at all times to keep them from falling ill. And in true Darwinian fashion, with the antibiotics ubiquitous in the environment, the bacteria the antibiotics are intended to kill are evolving a resistance to those same antibiotics. Any bacteria that develop mutations that make them immune to the antibiotics survive, and those traits get transferred on to a new bacterial population. When this happens, the antibiotics lose their power for that particular strain.

So how do antibiotic resistant bacteria get to your plate? The unhappy truth is that in an industrial scale system of livestock production, it is common for fecal bacteria to contaminate meat and other animal products during slaughter and processing. And while proper cooking kills all bacteria (even the antibiotic resistant strains), it’s easy for cross-contamination to occur in the kitchen if people do not take extreme care to separate and sanitize anything that comes into contact with raw meat.

If people do get sick, antibiotic resistant outbreaks often have higher hospitalization rates. In the recent Foster Farms antibiotic resistant Salmonella outbreak, 40% of those who got sick were hospitalized, about twice the usual rate in outbreaks. To make matters worse, 14% of the infections in the Foster Farms Salmonella outbreak developed septic (blood borne) infections, compared with the usual 5% in a typical outbreak. Part of the reason that antibiotic resistant infections are more likely to result in hospitalization and septicemia is that doctors usually treat patients with their standard antibiotics first, and by the time they realize their not working, the infection has spread. Only then do they test for bacterial susceptibility and realize they need to reach higher up the medicine shelf for the stronger, less commonly used antibiotics.

If people do get sick, antibiotic resistant outbreaks often have higher hospitalization rates. In the recent Foster Farms antibiotic resistant Salmonella outbreak, 40% of those who got sick were hospitalized, about twice the usual rate in outbreaks. To make matters worse, 14% of the infections in the Foster Farms Salmonella outbreak developed septic (blood borne) infections, compared with the usual 5% in a typical outbreak. Part of the reason that antibiotic resistant infections are more likely to result in hospitalization and septicemia is that doctors usually treat patients with their standard antibiotics first, and by the time they realize their not working, the infection has spread. Only then do they test for bacterial susceptibility and realize they need to reach higher up the medicine shelf for the stronger, less commonly used antibiotics.

What’s even scarier is that now pathogen strains are developing resistance to multiple antibiotics. The bacterial strain responsible for the Foster Farms outbreak is reportedly resistant to several common antibiotics used in human medicine. Imagine the doctor who realizes that the arsenal of weapons usually available is now useless to treat what would have previously been a simple case of food poisoning.

As Susan put it, this dire situation is bringing us back to a pre-antibiotic era. “Nobody should eat dinner, get sick, end up in the hospital, and not be able to get treated.” And the longer we wait, the more resistant the bacterial populations will become. Susan warns, “If we don’t act soon, this is only going to get worse.”

As Susan put it, this dire situation is bringing us back to a pre-antibiotic era. “Nobody should eat dinner, get sick, end up in the hospital, and not be able to get treated.” And the longer we wait, the more resistant the bacterial populations will become. Susan warns, “If we don’t act soon, this is only going to get worse.”

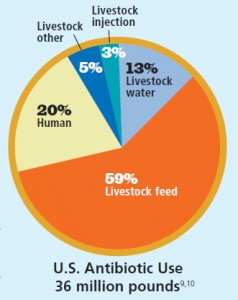

Can we really attribute antibiotic resistance to the use of antibiotics in the food system? What about overuse in human medicine? Shockingly, 74% of the antibiotics sold are used in animals. And as Susan explains it, if you wanted to create the perfect scientific study to test whether bacteria can develop antibiotic resistance, animal production in our country would be the perfect system: animals living inside, close together, in their own feces—the perfect conditions for bacterial growth and transfer. And research has shown the causality between CAFOs and antibiotic resistant strains: Lance Price and his colleagues have traced specific strains of antibiotic-resistant bacteria to livestock operations.

Is there any hope? Susan thinks so, but we need to act fast. In my next post, I’ll share Susan’s ideas for how we can reduce the prevalence of antibiotic resistance bacteria in our food supply.